Captured Moons are Very, Very Rare

Jupiter and Saturn are Absolute Units, the gravitational heavyweight champs of the solar system. Latest counts put their moon tallies at Jupiter: 95, give or take, and Saturn over a whopping 140. Of those moons, the majority are thought to be "captured" bodies - not created along with their planet, but formed elsewhere and ensnared into orbit when they strayed too close.

Clearly those gas giants just suck up every rock in the neighborhood.

...Or Do They...

Check out this moon orbiting a planet.

We could watch for a long while and not expect to see it wander out of orbit for no reason. Orbits are stable - till something intervenes.

The laws of gravity and motion are so symmetrical that you can't even tell if that video is running forwards or backwards. The physics would be solid either way.

If we don't expect that moon to wander out of a stable orbit...

then why expect it to wander into one?

Answer: we shouldn't. An ejection requires some outside influence "kicking the moon out" of orbit. A capture is its mirror image, and takes just as much outside influence to "rope it in" to orbit.

For some reason, we don't think a moon would fly out of orbit, yet we might picture it falling into an orbit. But they're two sides of the same coin.

Why Captures Don't Just Happen

One might think a mass could drift by slowly, close enough for Jupiter’s huge gravity well to pull it in, but no. That gravity well gives as much as it takes. Anything slow when far away will be accelerated by that massive gravity, and too fast by the time of its close approach. It will whip right back out.

But that's a random path, what if you could perfectly aim a mass just right to "land" in orbit? Answer: Then we'd have shot projectiles into Lunar orbit decades ago. No spacecraft has ever passively "coasted" into lunar orbit. Any ship traveling to the moon first needs to get near, and then fire its engines to slow down enough to be bound in orbit.

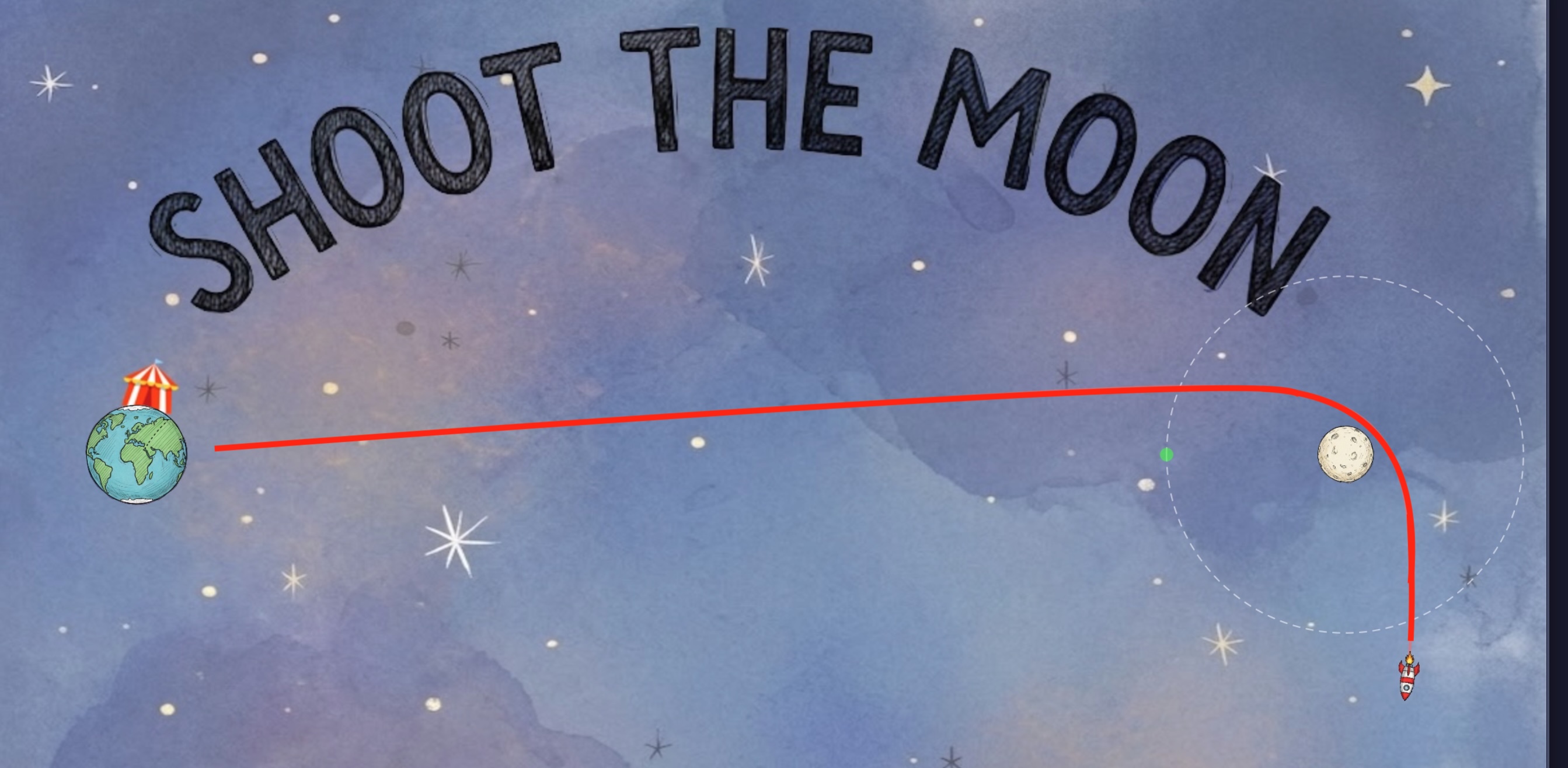

I'll give you a cannon on Earth with any muzzle velocity you want. Your cannon may certainly get over Earth's escape velocity, you can make a single flyby and overshoot the moon, and you can surely hit the Moon directly. You can try to put just the right "touch" on it, like a rigged carnival game, but you'll never find the sweet spot that lands your projectile in a stable lunar orbit.

The problem in this rigged carnival game is your excess energy. The point where the Earth & Moon's gravity are equal is called "L1" - the flat spot between their two gravity wells. A projectile atop this ridge, allowed to roll down will be carried right over the next ridge unless it does a breaking burn. A body at the L1 point has too much potential energy relative to the moon. When that potential converts to kinetic energy, it's above the moon's escape velocity.[1]

Here. Try it yourself:

This image from the game tells the whole story:

The chances of a planet adding a moon via capture are vanishingly small, and take an insanely rare alignment of events.

Astronomers have seen temporary asteroid captures lasting a few orbits, but in centuries of astronomical observations, have never observed the establishment of a new permanent moon - not anywhere in our solar system. Jupiter's moons were studied so precisely, that their timing was used in the earliest measurements of the speed of light - over three centuries ago! Consider what has been observed over this time - rare phenomena like comet impacts. We've seen Jupiter's great red spot evolve over centuries. The solar system has changed in human history. But moon captures are still too rare to occur in that time span.

You can try to create a capture yourself. The gravity sim, Stardust Studio, and all the scenarios referenced in this article are freely downloadable via links below.

Then what does rope asteroids into orbit?

Gravity assists - but backwards. You've perhaps heard of Gravity "slingshots" that boost probes toward the outer Solar System. A Gravity assist during capture works the same way, in reverse, slowing the asteroid. In each case, it requires 3 bodies, the "traveler" (asteroid), the planet it orbits, and the third body - the "disruptor". It alters the situation by giving the traveler a kick in one direction or another.

Demo of Gravity Assist, to Accelerate

In this animation, the small asteroid swings by the large planet and boosts its speed 30% relative to the Solar System.

A Non-capture

Asteroid (white) flies by Planet (orange). There is no assist, no third body to brake it. It is on a "hyperbolic" orbit. (A hyperbolic orbit isn't an "orbit" as we normally think of it, it means the object will escape). Its trajectory curves but there is no capture.

A Capture

Asteroid (white) flies by Planet starting with the same trajectory. This time, passing rogue planet (blue) is the "disruptor", Its passing is timed perfectly to combine with the gravitational influence of the orange planet, and the 2 planets together curve the asteroid into an orbit around orange.

That precise alignment is a cosmic hole in one. I might've been up all night finding a working path for the blue "third body". Instead I got it quickly via symmetry. I started with the asteroid in orbit around Orange, fired the blue planet at it, to disrupt the orbit, and let them all fly off, then used the result as new starting conditions - with directions reversed. I ran from there and voila, captured moon.

While Jupiter and Saturn need outside help roping in even the slowest passing rocks, speed definitely matters, and the slower passerbys are more likely to be captured. Consider interstellar wanderers like Oumuamua and currently 3/I Atlas - the latest identified interstellar visitor, now screaming through the Solar System at 60 km/s, and accelerating. The only remotely possible capture scenario would be Jupiter providing a massive gravity brake, bringing an interstellar asteroid below solar escape velocity, but such trajectories have already been ruled out.

Likewise, those travelers experienced some one-in-a-jillion ejection propelling them beyond their star's escape velocity. Not only that, but on a rare trajectory bringing them into another star system (ours).

In a future article, we'll break down an interstellar ejection scenario: What would it take for our solar system to send our own "Oumuamua" toward another star such as Alpha Centauri?